If you are a fan of the Vikings you will have heard of a shield wall and a shield maiden, but what is a shield boss? A shield boss is the central part of a shield, (Fig 2) and this one has definitely been in the wars. (Fig. 1, left) It belongs to Worthing Museum and came from a Saxon warrior graveyard in Sussex. It is around 1500 years old, and although it now looks completely unrecognisable, it was once similar to the image in Fig 1, right. As we can see, it’s completely corroded and cannot be restored, so what can be done when an object is not what it originally was?

When is a shield boss not a shield boss?

Worthing Museum has several complete and well preserved shield bosses, so this one won’t go on display. Its’ new function will be for research – it is now a very interesting historical document! Its’ features can tell us a number of things:

- The shape – it fits into a recognised category (Dickinson and Heinrich 1992) and will add to historical knowledge of the Saxon people it belonged to, showing how far they travelled, and maybe even where they came from.

- It will add to the history of the Sussex area.

- There may be ‘mineralised organic’ remains of wood or leather attached to the back which could reveal more about the shield itself. (‘Mineralised organics’ are fragile remains of organic matter preserved within the corrosion).

- There could be some remaining metal and features such as rivets – analysis could be carried out by future researchers.

Taking all this into account, I drew up a battle plan to preserve the boss.

The Battle Plan

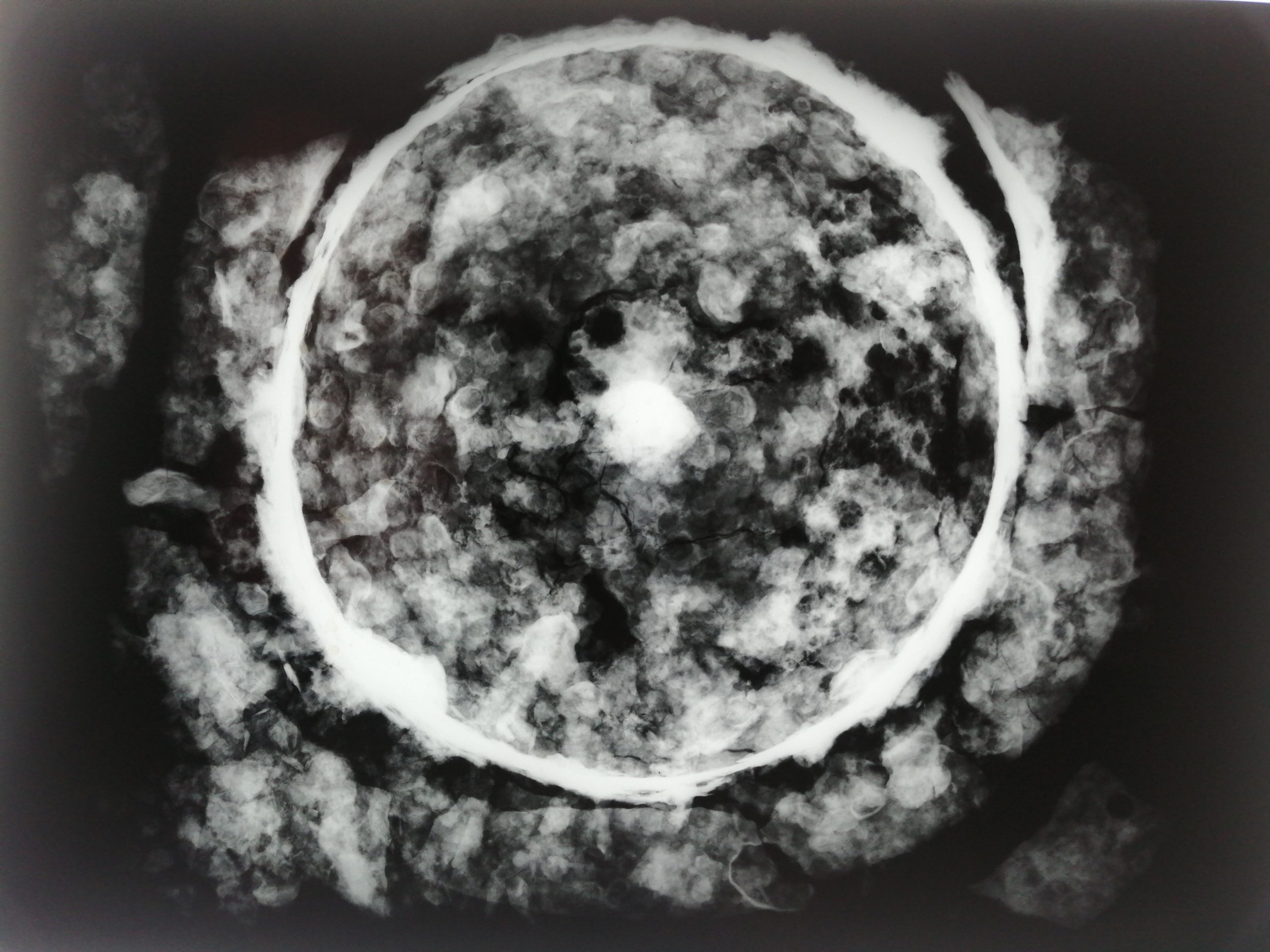

The first step was to x-ray the object, which confirmed that it was mainly held together by corrosion and soil. (Fig 3) The x-ray also showed there was still some fragile metal remaining around the ‘walls’, suggesting that a corrosion inhibitor should be included in our plan.

The second step was to take detailed photographs – you can never take too many! If any of the tiny fragments collapse, the photos will help to reconstruct the jigsaw puzzle. (Fig 4)

The Strategy

- Investigate how much of the object is still metallic by using a weak magnet. This indicates where to apply the corrosion inhibitor.

- Gently explore how much of the outer layer consists of loose fragments, and how much is still attached to the underlying layer. If some fragments are resting on others, I will need to consolidate (strengthen) the underlying layer first, before attaching the loose fragments on top. (Fig 5)

- Take note of any mineralised organics attached to the surface.

- What to do with the soil? Iron corrosion will grow to encompass its immediate environment. In this case, the soil and corrosion have fused, and removing it would cause serious damage to the boss. In this case, the soil will be left in place until the loose fragments are consolidated, then it can be reconsidered.

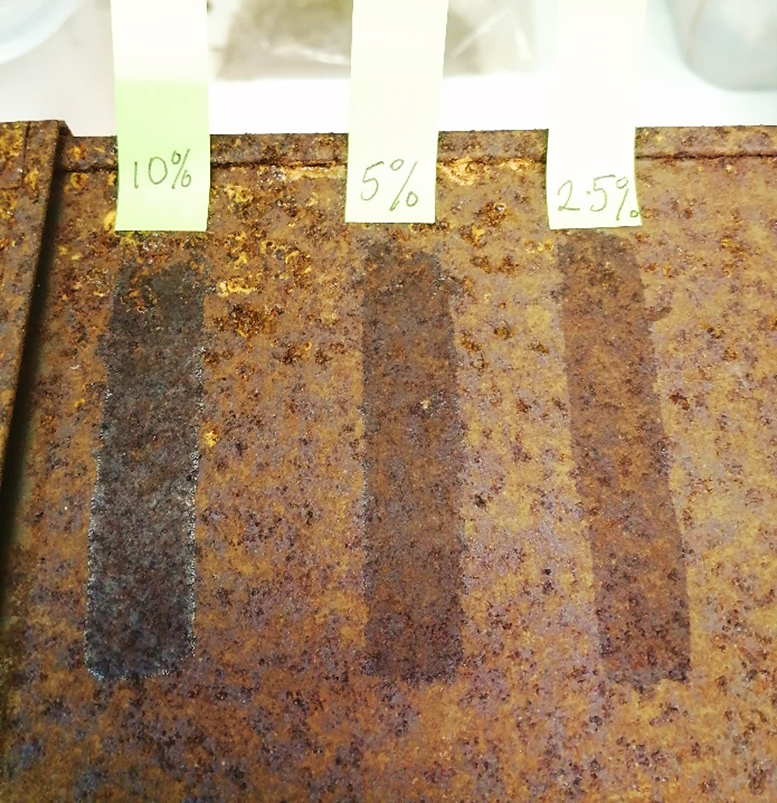

- The remaining iron may still corrode, so tannic acid can be used as a corrosion inhibitor. The recipe and method set out by the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI note 9/5) is a go-to. It will darken the surface, however the colour change is acceptable. (Figs 6 and 7)

- Begin to consolidate the loose fragments from the centre. Consolidation will be done with Paraloid B72TM in 5% – 20% solutions with a solvent of 50:50 acetone: IMS (industrial methylated spirits).

Use the higher concentration for broken and loose fragments. For cracks, apply the lower concentration solution by dripping small amounts from a brush and allowing it to travel along the cracks by capillary action.

- If there are mineralised organics, what is the safest option? They could be left in position or removed to safe storage.

- When the outer layer is stable, it can be turned over and gently rested in a TyvekTM cushion (lint and acid-free ‘fabric’) loosely filled with polystyrene balls for support. Then the inside can be assessed and the next steps planned.

Let’s regroup!

This is a good time to evaluate the progress of the treatment and consider any further actions. If the shield boss is now stable, it should be stored in a low relative humidity environment (below 20% RH) and checked regularly for signs of corrosion. This will be a challenging treatment, requiring a steady hand and patient approach, and it may take some time to complete. If you are interested in archaeological conservation see the ‘Further Reading’ section below.

Tags: Saxon, shield boss, armour, arms, history, Anglo Saxon, archaeology, iron, corrosion, metal conservation, Worthing Museum,

Click here for : Condition and Treatment report: Shield Boss Object is shown with the full permission of Worthing Museum.

References:

CCI note 9/5. https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/tannic-acid-rusted-iron-artifacts.html

Accessed 5/12/21

Dickinson T, Heinrich H. (1992), ‘II: Typology of Metal Shield Fittings’. Archaeologia, 110, pp 430 doi:10.1017/S0261340900028137

Further Reading:

Laird, J. Viggers, M. (2014) ‘Object biographies: An Anglo Saxon shield boss from Magdalen Bridge, Oxford.’ https://britisharchaeology.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/east-oxford/ob-shield-boss.html accessed 5/12/21

Caple, C. (2021) ‘The Challenges of Archaeological Conservation’, in Caple C, Garlick V. (eds) Studies in Archaeological Conservation. London: Routledge

Figures – All images of the shield boss were taken with the permission of Worthing Museum.

Fig 1 left – Author’s own

Fig 1 right – https://geheugen.delpher.nl/nl/geheugen/view?coll=ngvn&identifier=RMO01%3A008541 Accessed 6/12/21

Fig 2 – http://thethegns.blogspot.com/2013/01/anglo-saxon-and-viking-shield-words.html Accessed 6/12/21

Fig 3 – X-ray. 3mA, 85 seconds, 90kV

Figs 4 -7 – Author’s own.